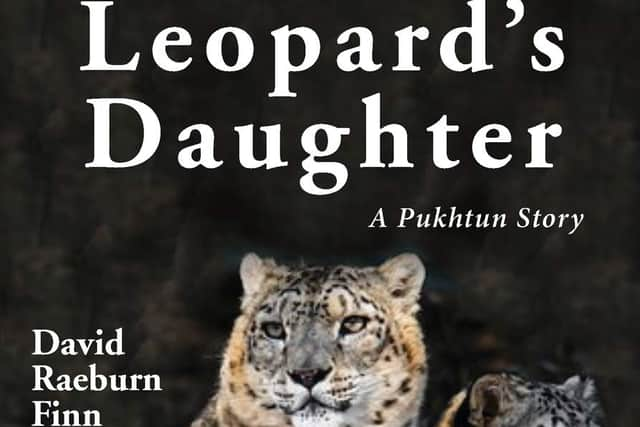

MUST-READ OF THE WEEK: THE LEOPARD’S DAUGHTER: A PUKHTUN STORY

This article contains affiliate links. We may earn a small commission on items purchased through this article, but that does not affect our editorial judgement.

New romantic thriller The Leopard’s Daughter: A Pukhtun Story by David Raeburn Finn is an engrossing and insightful novel set during the War in Afghanistan and which lays bare the horrors of military conflict.

It has only been a matter of months since the War in Afghanistan, the US-led occupation which spanned two decades, finally came to a close.

It is best to leave it to future historians to determine the success or otherwise of this prolonged military intervention but whatever the final verdict one thing is clear: the war caused untold harm to the country and its, largely, peace-loving people.

I say “untold” because, as is always the case, the ‘official’ figures on the number of civilian casualties is, to say the least, highly questionable.

An independent analysis conducted by US-based pacifist and social justice organisation Code Pink estimated that it resulted in the deaths of more than one million Afghan and Pakistan citizens. This is in stark contrast to the US’s own estimate of fewer than 40,000 casualties.

However many people died, the vast majority were innocent Pashtuns as opposed to bloodthirsty West-hating Islamic fundamentalists and this is something that Canadian author David Raeburn Finn had firmly in his mind when penning moving new novel The Leopard’s Daughter: A Pukhtun Story.

It follows the story of Mohammed, a skilled but politically naïve Denver surgeon of Pashtun descent who, during the War in Afghanistan, joins US Special Forces as a frontline medic at a secret base in Kunar, Afghanistan.

There, in a story of charged racial politics and clashing cultures, Mohammed can’t but help get drawn deeper into his roots.

At first, he prays and converses with Afghan civilians, whom he finds to be both spirited and generous despite their hardships.

Soon, however, he finds himself having no option but to physically defend them—not from Taliban troops but from his follow US soldiers, who have a sickening bloodlust fuelled by xenophobia and a gross disrespect for the rules of war.

Little does he know, however, that his Muslim faith and background already have him marked on a secret CIA watch list dubbed ‘OWL’ (Others Watch List).

After surviving a cross-border ambush that was specifically targeting him, thanks to the unprompted assistance of a nearby Pashtun family, Mohammed calls upon his medical knowledge to save the life of Shahay, a young widow who had bravely helped fight off the attackers before being injured.

Mohammed accepts the invite of Shahay’s brothers to tend to her recovery at their Bajaur home and now welcomed as an esteemed guest, he soon becomes drawn to them, especially Shahay, known as the “Leopard’s Daughter”.

His visit, however, unknowingly sets in motion a CIA private contractor operation aimed at discovering Mohammed’s true motives and allegiance.

Before it closes, it will bring tragedy and gruesome deaths to the residents of Bajaur, raising the question of whether these innocent deaths can ever be forgiven.

The premise of this story, then is immediately promising—a fast-paced thriller with a romantic subplot that both softens the bleak scenario while at the same time only ramping up the peril and stakes.

Yet it must also be stated that The Leopard’s Daughter: A Pukhtun Story is also undoubtedly an anti-war novel, highlighting through its well-drawn and engaging characters, keen observations, and thoughtful plotting, the devastating impact of the US military intervention.

Not very well-known in the western world, the Pukhtuns are part of the broader Pashtuns ethnic group of Afghanistan and Pakistan, separated from the wider Pashtuns only by their dialect.

Finn is the perfect author to bring us into this hidden culture, essentially unknown to those in the West in any meaningful way.

Firstly, he has previously co-authored A Brief Introduction: Believing Women In Islam, which considers the Quran’s teachings about women and patriarchy and which has been nominated for the prestigious 2022 Grawemeyer Award in Religion.

Secondly, he is a keen scholar on the Pashtun people, counting many elders as friends and whom he interviewed while researching his novel.

Thirdly, he comes from a military family and keeps abreast of American foreign policy and politics, approaching it with the enquiring mind one would expect of a philosophy teacher.

This is why, then, the alien world he conveys seems so concrete and lived in, providing a vivid representation of Pashtun culture.

This wider context is what is missing from the sterilised reporting of war, and what makes you understand better than anything else that beneath the language and religious differences there are just people trying to keep things going amidst a climate of uncertainty and fear.

The novel avoids a reductionist approach of simply swapping the hats and calling US troops the bad guys and the natives the heroes, but does not flinch from pointing out that many of the atrocities committed in the name of peace, as well as the blunders and cover-ups, came from the American side.

One passage perfectly sums this deplorable aggressor mentality up, with Mohammed concerned over innocent loss of life and a fellow American, Montoya, telling him “All Afghans are hostiles”.

“When Afghans kill Afghans, it’s a feud. When we kill them, we’re an invader. Any Afghan, Pashtun or not, will fight us. The more hostility, the more need for our military. Success means bodies. For us, improving body count means anyone who winds up dead is a hostile.”

“Mohammed winced. ‘Innocents?’ Montoya shook his head. ‘Innocents? Where’s your cynicism? Why are soldiers here? Soldiers kill people. Promotions come from bodies. Trust me. Whether our guys wanted them dead or they’re collaterals, they’ll be hostiles. Innocents? There can’t be any.’”

With such powerful scenes and incisive dialogue, it is impossible not to rethink the propaganda the West has been fed for so long over the Afghan war and, by so doing, discover enormous empathy for the Pashtuns.

The novel also has very strong themes of race and culture division, how societies interact at macro and micro levels and how individuals (such as those in the military) can negatively shape the outcomes of people’s lives.

The Leopard’s Daughter, however, is far from entirely bleak. While there is much violence and horror, equally there is love and tenderness in Mohammed and Shahay’s attempts to build a relationship in a world that is being torn down around them.

The setting of the book, the Afghan mountains with their beautiful colours and skies, also make this book feel like a compelling work of cinematic fiction and one that deserves to be adapted for the big screen.

Cleverly constructed, with shifting narratives, points of view, settings, motives and back-stories, it is an accomplished piece of writing.

I would say the book is worth the time of anyone, thriller fan or otherwise, who wants to gain a more balanced picture of world affairs, being a forceful anti-war novel that restores the humanity to the West’s perceived ‘foes’.

The Leopard’s Daughter: A Pukhtun Story by David Raeburn Finn (Lemahouse) is out on Amazon in hardcover, paperback and eBook priced at £26.95, £17.99 and £9 respectively. For more information, visit www.davidrfinn.com.

Q&A INTERVIEW WITH AUTHOR DAVID RAEBURN FINN

Author David Raeburn Finn is the first to tell you that he is neither a spokesperson for the Pashtuns nor an official expert on their culture, yet in his new novel The Leopard’s Daughter: A Pukhtun Story he vividly recreates their war-torn world to provide readers with a more rounded representation of the two-decade War in Afghanistan.

Q. The Leopard's Daughter: A Pukhtun Story is very much an anti-war novel. What is your own view on the War in Afghanistan?

A: It was waged under false pretence. The US had already prepared for war in April 2001 (Jane’s Defense). The underlying rationale? The CIA had noted previous Russian geologists’ estimate that Afghanistan had untapped mineral resources worth in the trillions.

The pretext: Bin Laden didn’t orchestrate or initiate 9/11. Planted ‘evidence’ (a video) that he planned 9/11 is the source of jokes throughout the subcontinent and the Middle East.

Virtually all that has been written about the war fails to acknowledge the testimony of the people most affected by the war, the Pashtuns. The war was borne of ideologically induced stupidity, brought on by false pretence, conducted with relentless and purposeful mendacity, fought badly by bewildered Western soldiers and directed by hopelessly inept military leaders of every Western nation who understood neither the enemy nor their own weaknesses.

Q. What do you think that readers will gain most from reading the novel?

A: I hope that readers of The Leopard’s Daughter: A Pukhtun Story may feel they’ve glimpsed into the hearths and realities of those most affected by the war in Afghanistan and Pakistan, the Pashtuns of these countries.

Q. The novel provides a vivid depiction of Pashtun culture. How would you sum up this culture to those unfamiliar with it?

A: The Pashtun culture is at least 4,000 years old, brought late to Islam, and socially and religiously conservative by nature. In practice the Pashtuns/Pukhtuns esteem the honour of family and tribe, an honour requiring support for the worthy aims of other families and tribes. Honour is maintained by observing what Pashtuns call “Pashtunwali”, the code of Pashtuns. The Leopard’s Daughter: A Pukhtun Story, offers brief introductory notes to the complexity of Pashtunwali.

Q. How did you go about researching your novel?

A: I peppered Pashtun friends and correspondents with questions. They included a brilliant Cambridge anthropologist, a Kabuli mujahid of the Soviet Afghan war, a well-educated polyglot Swati Pashtun living in Canada, a gifted and humane Pashtun PhD student and blogger writing under the handle of ‘Orbala’, (Butterfly), a Pakistani journalist whose contact with the Taliban and unflinching courage saw him assassinated by Pakistan’s ISI, the most senior Pakistani journalist and news editor famed for his interviews with Osama bin Laden, and many more.

Q. Why did you choose a Muslim American soldier as your novel’s protagonist?

A: Mohammed is one of two main Muslim characters in The Leopard’s Daughter: A Pukhtun Story. Soldiers are schooled in killing. Regrettably, some take pride in the deaths of supposed enemies. By contrast, Mohammed is a prodigiously skilled surgeon dedicated both professionally and as a believing Muslim to do no harm to innocents. Disposed to help, he performs difficult surgery to deliver the child of an avowed enemy. Because he’s a Muslim of Pashtun descent we are welcomed with him to the hearths and gathering places of Pashtuns..

But as a Muslim of Pashtun descent, targeted with lethal suspicion from the beginning by the CIA’s OWL program (Others Watch List), he is a victim of the very country he serves in spite of his rare qualities.

Most soldiers serving the West’s war in Afghanistan deserve sympathy. Trained to kill, they found themselves led by an inept Pentagon, set amongst civilians whose customs they didn’t understand, whose language they didn’t speak, whose conduct was opaque. Amongst returning veterans from Af-Pak the frequency of PTSD, suicide and family chaos marks massive moral injury.

Q. The novel features a love story between the protagonist and a Muslim Pukhtun woman. Why did you think this was important to the wider narrative, thematically?

A: The Leopard’s Daughter, the heroïne Shahay, is both a victim of Western ideologically induced stupidity and a survivor. She comes to love an innocent American soldier whose brilliant surgical skill has saved her but who, unawares, brings catastrophe to her and her family.

She is all Pashtuns, believers to whom an unbidden, undeserved war was brought. She is a widow who suffered, yet overcame her wounds to find hope and finally the love of a fellow believer and equal victim.

She represents Pashtuns prepared to accept the worth of an individual while ignoring the nation from which he comes.

Q. What has been the feedback for the novel that you are most proud of?

A. I’m pleased at unexpected comments that the novel’s descriptive scenes appear designed for cinematic adaptation even if that wasn’t intended. In The Leopard’s Daughter: A Pukhtun Story I imagined Mohammed’s platoon under fire, a surgeon/medic treating a mortal wound in the field, the impact on him of losing comrades; I imagined a young child learning to care for and become companion to a snow leopard cub, and that five-year-old girl, now become an adult, fighting for her honour and her life.

Q. Propaganda is nothing new and is often discredited in the years following military intervention. Why, then, do you think people still choose to accept a partisan, politically motivated narrative, and how can this best be challenged?

A: War propaganda in English-speaking countries divides into three separate time periods: making ready, during, and after. Propaganda consists of systematic distortion and outright lies. Regrettably, the Tonkin Gulf, Mai Lai and WMDs signalled that the press is, with exceptions, willing to side with liars. So, worldly readers are increasingly abandoning propaganda spewers of all stripes. Even less-critical readers are catching up. I gather the former Manchester Guardian now claims to be read by what, 100,000 readers? Slipped a bit has it?

The New York Times recently wrote a piece about a Chinese tennis player being raped by a senior member of the Chinese Communist Party. She’d never claimed rape. The tennis player, with devastating courtesy, invited the NYT in future to contact her to confirm what they wished to write about her. A useful rule for newspapers at war, invariably followed by giants like Robert Fisk, Patrick Cockburn and Seymour Hersh, is to check with the enemy when their atrocities are alleged in the warring press.

Q. You come from a military family. What wisdom did you learn about the realities of warfare this way?

A: We were young when our father was demobbed from the Canadian Army after serving in Britain and Europe. We lived in a community of homes purpose-built for veterans. None spoke of combat, none of the war. None claimed heroism for himself or his fellows. Watching the telly with a friend, his father sometimes burst out with bloodcurdling screams. PTSD. Two mates blown to pieces by German shells in Italy’s trenches, we were told.

I wonder whether our modern tendency to refer to returning military personnel as ‘heroes’ is misguided: doesn’t it imposes a burden of expectation many of them feel is undeserved? Too many seem unable to bear it, and harm themselves or descend into defeated lives. Modern ‘heroism’, I suspect, is propaganda all too hollow.

Q. With this book now published, what can we expect next from you?

A:Two projects—one fictional, one historical—will continue to find me amidst the Pashtuns.