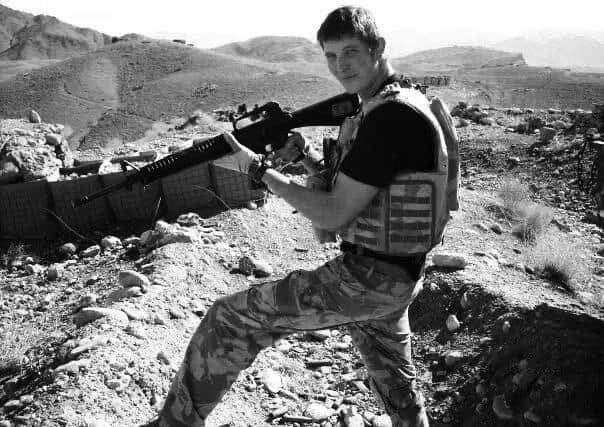

‘It’s all about empathy’: Ex-Green Beret who lost his legs in Afghanistan helping veterans with their mental health

and live on Freeview channel 276

It was, as Gregg reports, a beautiful day. Out on patrol in Helmand Province, Afghanistan as part of his tour in support of the Royal Marines, Gregg was on the lookout for roadside IEDs (improvised explosive devices) when he came under enemy fire. Nothing out of the ordinary, he’s quick to explain. He headed off in search of higher ground.

“The next thing I remember, I couldn’t see for the dust in my eyes and my ears were ringing,” says Gregg. “It was disorientating, almost like a film. I patted myself down and realised I’d lost a finger and thought ‘oh, that’s pretty bad’. Then I realised there was an issue with my legs. I could hear the lads yelling to stay still as they checked for secondary devices.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“They were very professional and took their time even though your gut instinct is to go and help your comrades,” adds the East Lancashire-born Gregg, now 38. “It felt like a lifetime because of the pain and the realisation that this wasn’t a ‘dust-yourself-down’ sprained ankle, it was a ‘the helicopter’s coming and you’ll be lucky to survive it’ kind of incident.

“I was in and out of consciousness for the next few days, only really seeing the odd nurse saying ‘everything’s alright’,” he continues. “I came to in Birmingham with my mum next to me, which was a bit disorientating. The doctors were dead realistic with me, which was good, because part of me was thinking ‘I’ll be back in Afghan in a couple of weeks’.”

A life upended

Far from a return to Afghanistan, Gregg instead faced life as a double amputee. A fortnight from the end of his first tour of duty, he had effectively had both legs blown off after treading on a bomb, his left limb shredded to pieces just above the knee and the right just below it. Married and a father-of-two, the 24-year-old’s life had been upended.

In a single second, he went from elite commando famed for 30-mile hikes in Dartmouth, to a veteran. For a man whose life was the Army, it was tough.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“I was that kid who was inspired by people coming into the careers fair at school promising adventure!” says Gregg. “I loved the sound of it and I was in the Cadets, so the Army was the perfect environment for me. It taught me discipline and how to keep my mouth shut, but it also showed me that, if I worked hard, there were opportunities.

“I worked hard,” he adds. “I was immature when I joined and I’d never really engaged with education before the military, so it was an all-round good experience for me. The camaraderie was great too: for the first time in a while, I had a positive social identity as part of a group. I knew what was expected of me and I didn’t want to let my muckers down.

“When I went on the commando course, I knew that would be a guarantee I’d be going to Afghanistan because of the operational intensity back then in 2007,” Gregg explains. “It’s strange to reflect on it now as a father, but that only sharpened my desire - I wanted to test my skills and do what I was trained to do. I was ready for action and wanted to play my part.

“It was everything I expected and it sounds naive, but initially it was every boy’s dream: any weapon system you fancied, fast jets, explosions. Reality sets in very quickly though; we had a death early on and a few IED blasts, so you couldn't help but grasp the significance of the danger we were operating in. There were constant reminders, no respite.”

Finding his feet again

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdInitially too traumatised and medicated to realise the extent of his injuries, it wasn’t until three days after the detonation that Gregg fully grasped the life-changing nature of his experience. But, from there, he was focused on recovery. Given state-of-the-art prosthetic legs, he was the first person in the UK to be fitted with bionic bluetooth-controlled Genium X3 knees.

Designed by the US military, the prosthetics were fitted at Lancashire Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trusts’ Specialist Mobility Rehabilitation Centre in Preston. Funded by the Ministry of Defence, the £70,000 carbon fibre, steel, and aluminium legs enabled Gregg to run again as well as use tailored driving and cycling functions.

And, despite threatening to slip into the cyclone of bad habits and debilitating poor mental health, Gregg steeled himself to embark on a rejuvenating recovery campaign alongside his friends and family, regaining his fitness and reaping the rewards. Eventually, he became lead physio at the rehab centre which had helped him, supporting patients in a similar situation.

“The reality soon sank in and I met other amputees, which was great, then I started my rehab,” says Gregg. “I knew my military days were over - I’d always been snotty about meeting fitness standards and was the first to tell someone they shouldn’t be there if they couldn’t make the grade, so I knew there wasn’t room for people with injuries.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“It was mentally draining to be sat there thinking ‘where do I fit in?’” he adds. “All of a sudden, it wasn’t quite as simple as sticking your trainers on and going for a run. I struggled and developed some poor coping techniques around alcohol and pain medication, but I was lucky to have good people around me as well as positive role models.

“I got stuck into things like rowing and golf, which I’d never done before, and they were a really great outlet for me, which led me to explore mental health. I was only 24, so all my mates and my wife were working and I’d almost felt retired. That’s why getting a job at the prosthetics centre was so good for my self-esteem.”

Creating the C-Card

Also working with Walking with the Wounded to help ex-service personnel to regain their independence, thrive, and contribute in their communities, Gregg cultivated a real passion for aiding mental health recovery. And his coup de grace was his groundbreaking ‘C-Cards’ for veterans in immediate mental health danger.

With their nine steps based on a similar paradigm to the famous emergency evacuation ‘9-Liners’ used by soldiers on the front line, the C-Cards were designed in collaboration with Darren Clare from the Bolton-based creative agency Portfolio and gave veterans something familiar to use when in crisis.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“I was interested in how I could help, which is how I became a mental health practitioner working with veterans in the first place,” says Gregg. “I was passionate about sharing resources, so I designed the C-Card - in the military, we use 9-Liners so that, when the s*** hits the fan, everyone’s calm and can cover every eventuality.

“We needed that for when people were spiralling,” he adds. “And I wanted something veteran-specific, so Darren helped me knock something up which would look familiar to someone from the military and create immediate trust. It’s about empathy: men and people in the military are quite harsh on themselves, so being kind and patient is vital.

“I love the work and, selfishly, it helps my mental health, too,” says Gregg with a smile. “Seeing that penny drop for someone is so inspiring.”